Who was it that first defined news as the ‘first draft of history’? This very bright observation was attributed to the Washington Post publisher Philip M. Graham and the credit had remained with him for several decades. Even authentic documents quoted him as saying so.

But this notion was corrected on 30 August 2010 by the online news magazine Slate Editor at Large Jack Shafer who researched the internet archives of the Washington Post for some purpose and found that it was its editorial writer Allen Barth who first made this wise observation in 1943. The newspaper is not just the first draft of history but the repository of such very important information also, it seems.

But simply because newspapers are stacked in thousands of libraries, will they be of much use to people all over the world, for all times to come? In India, even now, a researcher will have to personally visit institutions and spend hours on the painstaking manual searching of dusty hard copies. How can this huge repository of knowledge and information be made available to people sitting in their homes and school libraries across the globe?

Digital technology is the answer. Anybody in a remote village in Kerala or Kashmir can now look into the collection of newspapers in the UK or USA, maybe even the first copies of the first newspapers of the 17th century. Thanks to archiving and digitisation, every single piece of paper can be made accessible to anyone, anytime, anywhere.

We too attach importance to archival materials related to the governance of the country. The records of panchayat boards are well maintained and preserved for the scrutiny of the people. They contain valuable information relating to the evolution of our culture, civilization and history and almost everything that happened in the past.

Governments spend a lot to see that this is done efficiently and digitized and networked. Well and good. But, what about ‘the first draft of history’ ? Will anyone living in Thanjavoor in Tamil Nadu be able to know how the ‘Free Press Journal’ of old Bombay reported the assassination of the father of the nation, Mahatma Gandhi?

This is not a question of just curiosity. There are scores of people – students, teachers, writers and researchers – who are looking for information on things that happened in the past. Are we doing them justice in this digital age? My experience is that the so-called ‘Fourth Estate’ is far backward and many are living in the pre-digital era. Even those who have digitised their archives do not make it available to the people, even for a price.

Let us see what the picture is, in the media of the developed world. Only a couple of days ago I received a newsletter from the British Newspaper Archive, an extension of the British Library, informing me that there are an extra 250,000 newspaper pages available. It also entices me to “Find out what’s been added, get newspaper access for just £9.95 and enter our competition to win a history book.”

In the British library, you can read almost all British newspapers dating from 1603. Around 600,000 bound volumes are kept in shelves, which if kept in a line will take 13 kilometres. Three hundred thousand microfilms too are archived, and that too will take another 13 kilometres.

Earlier when this collection was not digitized, visitors had to personally visit the library and cover the endless rows to find the newspapers they needed. Digitising started in 2011. Tens of thousands of files are added to the collection every day. They plan to digitize 400 million pages in ten years and hope to finish it in 2021.

The American Newspaper Association, formed by newspaper managements, is archiving historical newspapers from the 1700s–2000s. Over 3500 newspapers from across the United States can be accessed in their website www.newspapers.com. More than 95 million pages including articles, obituaries, photos, and birth announcements are available and millions of new pages are added every month.

The world’s biggest collection of newspapers may be that of the US Congress Library, the biggest library in the world. Millions of newspapers, books, photographs, manuscripts, maps etc. are stocked in the library that includes publications from 1690. It’s all US publications only and is made available for online viewing, free of cost. (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov).

The BBC preserves and makes available for viewing videos of all important events and happenings, interviews, broadcasts, speeches etc. (www.bbc.co.uk/archive/collections.html).

‘Archiving early America’ is where newspapers and historical photographs of 19th century America are archived- www.earlyamerica.com. The UK’s Guardian has made available its 1.2 million pages from 1791, for us to read, for a fee. In www.guardian.com you can search, identify, download and take copies of advertisements too. The archiving and retrieving system was opened up three years ago. There are some other private enterprises too in this field in the USA. Proquest Historical Newspapers is one such organisation and in its site www.proguest.com, issues of various newspapers from 1784 are available.

Another site where newspapers and old books can be found is http://archive.org, an international archiving organisation in which anyone can send and archive their collection of periodicals and copyright free books. More than ten million books and two million movies are already there, of which one million are free.

But what is our position in this area? We may not love to know that our colonial masters, the East India Company, were wiser and more advanced than us in this regard. They had in the very beginning of the printing presses in India ordered that three copies of each and every book printed here should be sent to their office, to be made available to the India House Library in England.

When it was found that this order was not effectively implemented, in 1897, they brought in an act to make it more effective. Thus was born the Press and Registration of Books Act, which is in prevalence even now. But whether our publishers are sending copies of books to officials designated for this purpose and whether any book is preserved as envisaged in the Act is a different question.

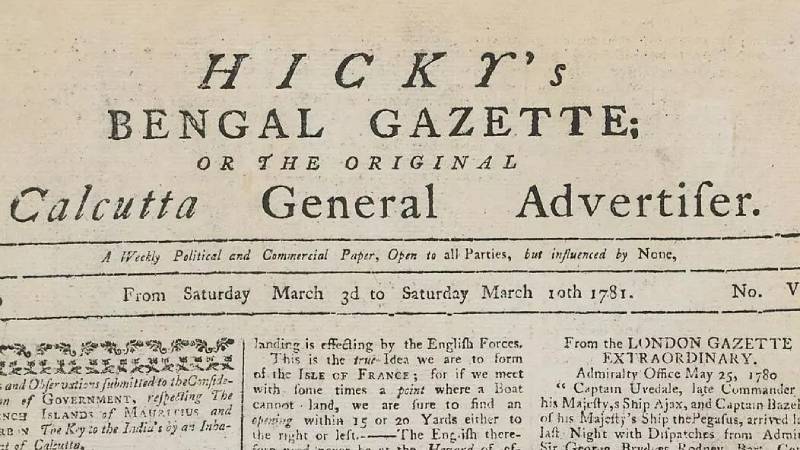

Some valuable publications, which are milestones in the history of the Indian media, are available on the Internet, thanks to a few unknown, sensible persons. The first Indian English newspaper, the Bengal Gazette, edited by James Augustus Hicky is one such. Not all the volumes, but luckily the front page of the edition dated 23 March 1782 is there in the section on the publication in Wikipedia.

A few pages of America’s first newspaper, the Boston Newsletter, launched 72 years before Hickey’s venture in India, can also be seen on Internet.

Unlike those in the developed world, we in India are permitted to read only very few first ‘drafts of history’.

I do not intend to argue that our media institutions are poor in archiving their content. Most of the big national newspapers have the print editions from the very beginning stored in their libraries. Several major newspapers have digitised their archives.

But no institution makes the content available for browsers outside their library. This is the case with regional language newspapers also. My attempt to find at least one newspaper institution with a quarter century history that has opened its digitised archives to browsers ended in utter disappointment.

A glance of the digital archives of the major newspapers gives an unimpressive picture. The Times of India has digital archives only from 2001. The Hindu has archives of the print edition from January 1, 2000 and web pages from 2009 only.

Readers of the Hindustan Times digital edition will not find a link to the archives section. Maybe they maintain only a physical archive. The Free Press Journal too, which has a more than eight decade history, does not mention anything about a digital archive on their website. The Deccan Herald archives are available only from 1st January, 2004.

We should be happy to know that a few non-media institutions maintain good collections of periodicals. The Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML), Teen Murti House, New Delhi is one such institution. The NMML houses a specialized research and reference centre library on colonial and post-colonial India. It possesses a very rich and varied collection of books, journals, photographs and other resource materials.

The NMML Library has acquired back volumes of more than 300 important newspapers and periodicals but they are all incomplete. The Library has a rich collection of material on microfilms and microfiche. It includes more than 19,000 microfilm rolls of private papers, missionary records, newspapers and old and rare journals and 51,322 microfiche plates of research materials. But sorry, there is no mention of any plan to digitise this precious collection.

The Madhavrao Sapre Museum of Newspapers in Bhopal, established in 1984, must also be mentioned. The Museum has nearly 40 to 50 lakh pages of reference material. But, here too you have to be physically present to read the rich collection. No mention of digitising.

The Digital Library of India, hosted by the Indian Institute of Science Bangaluru, in co-operation with CMU, IIT-H, NSF, ERNET, MCIT for the Government and 21 major participating centres is the only national institution that is taking up digitisation on a large scale.

The stated mission is to “create a portal which will provide free access to all available human knowledge”. As a first step, the Digital Library has been initiated with a free-to-read, searchable collection of one million books, available free over the internet. This portal also becomes an aggregator of all the knowledge and digital contents created by other digital library initiatives in India.

The demo version of the proposed new Digital Library of India website is supported by the Department of Electronics and Information Technology. Unfortunately, newspapers are not on the agenda. That is understandable because it is not possible for one such organisation to digitise the millions of pages of all Indian newspapers of all times.

I need to write a few sentences about the big service done by an enterprising individual in Tami Nadu, which will be model for the whole nation for ages to come. The Roja Muthiah Research Library was founded in 1994 to preserve and make use the personal collection of one individual – Roja Muthiah Chettiar.

Chettiar started collecting books in 1950. He earned a living by doing signboards. He fell in love with books and spent his earnings on buying books. He is said to have spent 16 hours a day reading and looking at books. During his lifetime, he built one of the world’s biggest private libraries.

Located in Chennai, it has now 300,000 items in its collection that reflect Tamil print heritage and culture spanning 200 years. A good portion of it is digitised. Take any piece of paper with some archival value to this instituition – never mind if it is just a film notice of the old period – and they will digitise it and return the original. This may be the only institution of this kind in India. Roja Muthiah Chettiar died on 4 June 1992.

Media students, journalists and researchers who most often need to look back in to the archives are anxiously waiting and praying to see a change of attitude among newspaper institutions. In most countries, it was newspaper associations which took the initiative in setting the ball in motion.

Newspapers, once sold in the market, are the property of society and part of history. Today or tomorrow, they will have to be made available to the general public who are, in the real sense, creators of all news and history. How long will we keep the creators of history from reading the ‘first draft of history’?

(N.P. Rajendran is a senior journalist in Kozhikode, Kerala and former chairman of the Kerala Press Academy. He can be contacted on nprindran@gmail.com.)